Wyoming’s four subspecies of cutthroat trout are native to the Cowboy State, and they’ve been around longer than any other trout species swimming in the state’s waters. In the late 1800s, prior to when Wyoming became a state, humans brought other fish to Wyoming. The Wyoming Game and Fish Department recently completed a genetics study of Yellowstone cutthroat trout. The goal was to see how genetically intact they are, and how much introgression — or genetic mixing — there is from other nonnative fish such as rainbow trout and other subspecies of cutthroat trout raised in hatcheries. A goal for Game and Fish is to expand Yellowstone cutthroat trout numbers in the state, and this work helps the department determine sources to replicate the closest genetic representation from the past.

Yellowstone cutthroat trout is one of four native subspecies in Wyoming. (Photo by Patrick Clayton)

FISH ALL OVER THE PLACE

The completion of the Transcontinental Railroad in 1869 played a big role in moving fish to what would become the state of Wyoming, whether it be brook trout from the east or rainbow trout from the west.

The U.S. Fish Commission was created in 1871 to investigate, promote and preserve the fisheries of the U.S.

“Fish were being put in all these different waterbodies, which created some tremendous sportfish opportunities, but clouded the situation with regard to cutthroat,” said Jason Burckhardt, Game and Fish fisheries biologist in the Cody Region. “Fish were being stocked into waters where surveys hadn’t even been conducted to know what fish were there.”

In the early years of the Wyoming Game and Fish Department, all of the state's native cutthroat species were simply referred to as "blackspotted trout." (Photo by Patrick Clayton)

To further complicate matters for Yellowstone cutthroat, Burckhardt said during that time there was a hatchery at Yellowstone Lake where fish were collected and distributed to a number of waters in the area.

“There were nonnative fish spread to waters, and also cutthroat put in waters where there were native cutthroat,” Burckhardt added. “It wasn’t just Yellowstone Lake. There were other hatcheries that were taking fish from a bunch of different sources and stocking them on top of a number of native cutthroat populations.”

And, even in the early years of Game and Fish, there wasn’t as much detail and science based on where fish were stocked compared to today. All of Wyoming’s native cutthroat subspecies were simply referred to as “blackspotted trout.”

BACK TO NOW

This study was a collaborative effort between Game and Fish, Idaho Fish and Game and Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks. Will Rosenthal is a graduate student at the University of Wyoming who has been involved in this study since 2021. Rosenthal said researchers began collecting samples for this project in 2018, specifically in the Wind River Mountains, although some samples used were taken as far back as 1999. Researchers sampled fish in Wyoming, Idaho and Montana — the primary range for Yellowstone cutthroat.

Game and Fish personnel record data from genetic sampling of Yellowstone cutthroat trout. (Photos by WGFD)

“What he’s been looking at is the influence of historic stocking on the genetic composition of the populations we currently have,” Burckhardt said. “Where do we have populations that are genetically intact, and where do we have populations that have been influenced by past stocking?”

Yellowstone cutthroat trout during sample collection. (Photos by WGFD)

More than 175 locations in western Wyoming were sampled, ranging from larger waters like the Greybull River to small, alpine lakes in the Wind River Range. Samples from more than 3,500 fish were taken from the Cowboy State, and more than 6,000 were sampled from Wyoming, Idaho, Montana and Utah. The samples from Wyoming included fish housed at the Ten Sleep and Auburn hatcheries, along with other subspecies of cutthroat trout and other species.

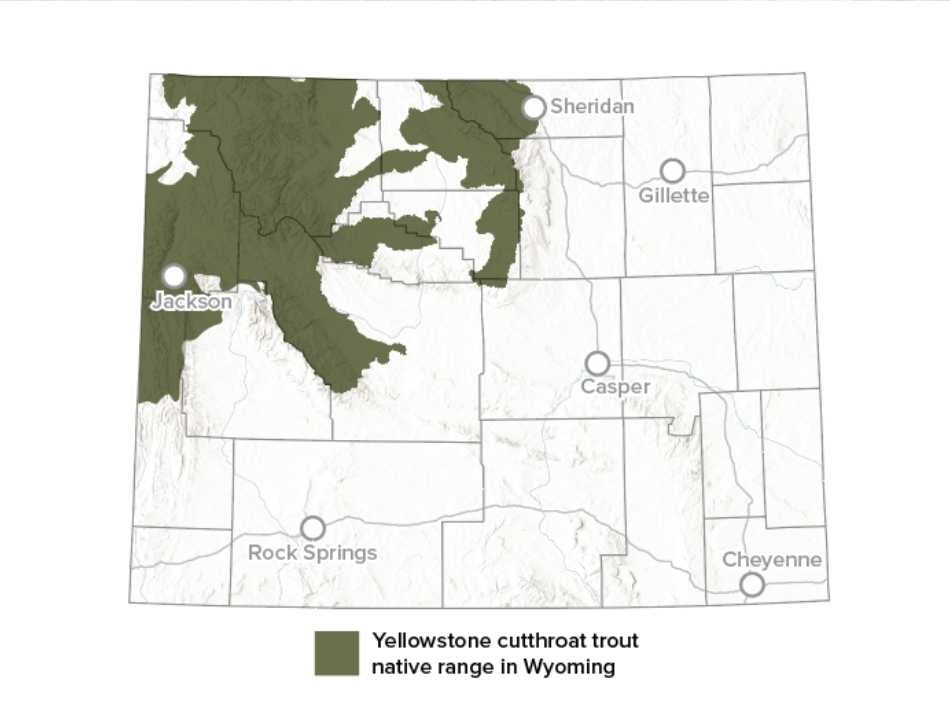

Yellowstone cutthroat trout native range in Wyoming.

“We wanted to understand what was going on in the entire range of Yellowstone cutthroat,” Rosenthal said.

More than 175 locations in western Wyoming were sampled for this genetic study on Yellowstone cutthroat trout. (Photos by WGFD)

The majority of the Yellowstone cutthroat populations in Wyoming with little to no introgression are in the Snake River drainage around Jackson and the Wiggins Fork near Dubois.

As for more introgression, Rosenthal said, “pretty much everywhere else.”

“There’s a little bit in a lot of places,” he added.

“Chances are if you are catching wild, Yellowstone cutthroat trout in Wyoming and it isn’t in the Snake River drainage or Wiggins Fork, there’s a chance there’s some amount of hatchery ancestry affecting that fish. It is still functioning as a wild fish and likely only constitutes ancestry from Yellowstone cutthroat from a hatchery.”

Rosenthal added that if you caught a Yellowstone cutthroat from an alpine lake in the Wind River Range, those fish aren’t native. When those lakes formed, there were no fish. They were stocked and continue to be stocked, although several currently sustain fish populations without continued stocking.

Rosenthal gave an example of the mixing of two species of cutthroat in Pumpkin Creek on the west side of the Bighorn Mountains that drains into Bighorn Lake. That population has some ancestry from Lahontan cutthroat trout, and there was genetic evidence of the mixing of the two species.

“It’s tricky to identify between Lahontan and Yellowstone cutthroat, especially if the fish is 10 or 15 percent Lahontan and the rest Yellowstone. It’s probably going to look like a Yellowstone cutthroat.”

MIXING ISN'T ALL BAD

Just because most of the Yellowstone cutthroat populations in Wyoming have ancestry from outside their home drainage doesn’t mean those fish are tainted or bad.

“It’s pretty easy to say fish with mixed ancestry are like a mutt and can’t do their jobs as well as a fish that isn’t mixed,” Rosenthal said. “An important thing to note is the difference between the two things we’re mixing is really small in this case.

"When you mix a rainbow trout and Yellowstone cutthroat and make a cuttbow, that is a very different fish. Those two have been separate species for about 10 million years. These differences of Rocky Mountain cutthroat — the four subspecies that we have in Wyoming — are much smaller in terms of time.”

To break it down a little more, Rosenthal used this analogy: “If we’re going to think of them as mutts, it is not like you’re mixing your Pomeranian and your Great Dane and making some kind of dog that doesn’t really know what it’s doing. It’s more like mixing your German shorthaired pointer and your German wirehaired pointer. Yes, they’re technically different, but that dog will still point. These cutthroats are really not that much different.”

NO SIMPLE ANSWER

Evidence of mixed genetics in fish can mean different things.

“One thing that can happen if you add fish from another population to the same species or subspecies, you can increase the genetic diversity of those populations and give them more genetic tools for evolving,” Burckhardt said.

“Another thing that can happen is if you overwhelm that population with too many of these fish that haven’t evolved in that given place, you might dilute some of these genes that have evolved in that place. We want to make sure our current cutthroat populations have the genetic tools necessary to evolve.”

This was one of the largest genomic projects that’s ever been conducted on a vertebrate species. The information is valuable for fish managers, but it doesn’t provide them with all the answers.

“The data set is huge and it has the breadth and depth to answer a bunch of questions, but also begs a lot of questions,” Burckhardt said. “It’s all complex and complicated, but we know we want to be proactive in what’s the most appropriate approach for our future restoration activities.”

THE SCIENCE BEHIND THE WORK

Tissue samples to look at the genetics of Yellowstone cutthroat trout consisted of a small portion of the tail or adipose fin, which was about one-quarter of the size of a pinky fingernail on a human hand. Techniques to get the fish included electrofishing, hook-and-line and gill nets.

Samples of adipose and tail fins from Yellowstone cutthroat trout collected for this genetic study. (Photos by WGFD)

Many of the samples collected in Wyoming were from Wyoming Game and Fish Department personnel in the Cody, Jackson, Lander and Sheridan regions. The U.S. Forest Service also helped collect samples. Will Rosenthal, a graduate student at the University of Wyoming who has been involved in this work since 2021, also collected some samples.

Samples were preserved in ethanol and brought to the lab, where the first step was to dissolve all of the proteins. That material was put into an incubator with protein-dissolving enzymes for 12-48 hours that turned the sample into liquid. DNA was then extracted and sequenced. High-tech machines read the DNA and provide data.

“It can compare that genetic fingerprint of a specific fish to the hatchery lines and other samples from the same population, or from fish in different areas, to get a sense of what proportion of that individual’s ancestry comes from different places,” Rosenthal said.

Rosenthal added it takes the better part of one year to acquire this information from each fish.

— By Robert Gagliardi