There aren’t many islands in Wyoming. According to Google, there are 35 named islands in the Cowboy State.

But from a fish culture standpoint for the Wyoming Game and Fish Department, there are 10 islands scattered throughout the state in the form of hatcheries and rearing stations. Those facilities spawn, raise and grow fish to bolster statewide fisheries. It is specialized work and a lot of factors are involved to achieve success.

New Zealand mudsnails are found in Wyoming, but so far not in any of the state's hatcheries and rearing stations. (WGFD photo)

One of those factors is keeping unwanted aquatic invasive species and fish pathogens out of those facilities. A lot of work led to that, and the work continues to ensure clean water and healthy fish.

“Why we’ve been successful with our culturing of fish, stocking of fish and good fisheries throughout the state is because we like to take a proactive approach,” said Guy Campbell, Game and Fish fish culture supervisor. “We want to know what’s going on in and around our surroundings at all times. It is our responsibility to look at the best information possible and continue to make improvements to stay up on issues.

“We can’t be complacent. If you do that, that’s when you fall behind.”

New Zealand mudsnails outcompete other species for food. (WGFD photo)

SNEAKY SNAILS

New Zealand mudsnails are an AIS found in Wyoming, and a big effort is being made to keep them out of the state’s hatcheries and rearing stations.

New Zealand mudsnails are not native to the United States and have been in Wyoming since the 1980s. The presence of these tiny creatures can impact ecosystems by outcompeting other species for food. There hasn’t been a major impact on fish populations due to New Zealand mudsnails in Wyoming, but monitoring continues. Game and Fish personnel know they don’t want these snails in their hatcheries and rearing stations.

“We’ve been taking a lot of efforts to work with our hatcheries to reduce the likelihood of New Zealand mudsnails making their way into facilities through natural movement,” said Josh Leonard, Game and Fish AIS coordinator.

New Zealand mudsnails are in the North Platte River near the Dan Speas Fish Hatchery near Casper. There’s concern the snails — or any other unwanted things — can get into hatcheries from discharged water coming in contact with receiving water — in other words water-to-water contact. Work was done at Speas, the Clark’s Fork Hatchery in the Cody Region and the Boulder Fish Rearing Station in the Pinedale Region to avoid that water-to-water contact.

Protecting water discharge into hatchery receiving water is the first phase of Game and Fish’s work at hatcheries and rearing stations to prevent AIS and fish pathogens from entering these facilities. The second phase is continued work to cover existing infrastructure. Some locations have fish tanks inside buildings, which is the most ideal scenario. However, some do not and the risks increase of bad things getting in the water and hurting fish. For instance, birds carrying AIS or pathogens can land in open-water areas like tanks and raceways. Birds and other animals that defecate in that water have the same effect. At some hatcheries with open water, small mammals pose threats such as raccoons, mink and otters.

“There’s always risks when tanks and raceways are not covered,” Campbell said. “We’re working on that and prioritizing all of our risks. We are working through it the best we can in an economically sensible way.”

At Clark’s Fork, Game and Fish is looking into using a programmable moving laser light at night and during low light to spook birds and other wildlife away from open raceways.

However, New Zealand mudsnails have an inside track to get into hatcheries and rearing stations. It has been documented that these snails can survive through a fish’s digestive system. If a fish is brought into a hatchery and has consumed a mudsnail, and then defecates in the hatchery water, there is a chance it could live and thrive in its new hatchery environment.

That hasn’t happened, yet Game and Fish is aware it could, and precautions are underway to prevent it. Part of the long-term future is going away from getting fish from other states, especially cool/warm-water species such as walleye, crappie, sunfish, etc. Plans are underway to build a cool/warm-water facility to raise fish at Speas in the coming years.

This drain at the Clark's Fork Fish Hatchery in the Cody Region helps ensure the water used in the hatchery is safe for fish. (Photo by Chris Martin/WGFD)

“Anything that’s transporting water has the risk of moving stuff, even if we can’t see it,” Leonard said. “We have these great facilities with clean systems, but all it takes is one fish that is carrying something or infected with something to get into a bunch of fish.

“We have to be cognizant of what’s in our own hatcheries, regardless of whether we bring in fish or not, so we’re not moving stuff around in our own state. That’s why we inspect our hatcheries every year at least once.”

BKD

There is no such thing as a good fish pathogen. Game and Fish is concerned about all of them, but the good news is there is nothing right now that puts the state’s sportfish population in serious jeopardy.

One pathogen that has caught the attention of Game and Fish is Renibacterium salmoninarum, the causative agent for bacterial kidney disease — known as BKD.

Cutthroat trout infected with bacterial kidney disease exhibiting petechial hemorrhaging on the skin. (Photo by John Drennan/Colorado Parks and Wildlife)

BKD is a systemic bacterial infection caused by a particular type of bacteria. All salmonid fish species are susceptible, and the disease typically occurs in fish 6 months old or older. Symptoms include abdominal fluid build-up and swelling, intestinal hemorrhaging, ulcers or abscesses in muscles, protruding eyeballs, blood blisters and lesions of the eyes, liver, spleen, kidneys and heart.

If Renibacterium salmoninarum manifests into BKD it can cause significant fish mortality. It also is vertically transmitted, which means it can be passed down from the parent to the egg.

According to Wyoming Game and Fish Commission regulations, there are four levels of fish pathogens: Emergency Prohibited Fish Pathogens, Prohibited Fish Pathogens, Regulated Fish Pathogens and Reportable/Notifiable Fish Pathogens. Pathogens are ranked in one of these categories depending on the severity of infection they can cause and the risk they pose to Wyoming waters and hatcheries.

Emergency Prohibited Fish Pathogens include pathogens that are usually not found in Wyoming but could have devastating effects on fish populations, resulting in a potential complete depopulation of a fish hatchery. On the other end of the scale, Reportable/Notifiable pathogens have the capability of causing mortality, but they can be treated and fish managers can work around them.

Renibacterium salmoninarum, which is found throughout the United States, is classified as a Regulated Fish Pathogen. This means while BKD can be a serious disease, potentially causing high mortality in captive-reared salmonid populations, a detection normally results in a depopulation of infected lots only.

To date, BKD hasn’t caused mortality in any of Wyoming’s hatcheries or rearing stations. However, there have been a few documented cases of Renibacterium salmoninarum in wild populations of fish in the western part of the state. Meadow Lake near Pinedale is one of Wyoming’s premier waters for grayling, and is a long-time source for Game and Fish to gather grayling eggs. Renibacterium salmoninarum also has been found in Colorado River cutthroat trout in some small streams in the Wyoming Range.

BKD in Wyoming hasn’t ever manifested into the actual disease where there’s been any or significant fish die-offs, but at some very low level the causative agent is there.

“We’ve historically used these wild populations to infuse the genetics of the fish we raise, and now it's becoming a lot more difficult as we need to be aware of any potential risk,” Campbell said.

Fish must be tested in order to determine the severity of BKD prevalence. However, the most accurate testing requires fish to be lethally sampled. In many cases, the number of fish required to get an accurate count of those infected could severely reduce the population in that particular water. Fortunately, the grayling in Meadow Lake have a strong enough population to sustain proper testing.

“Grayling in Meadow Lake did test positive for Renibacterium salmoninarum a couple of years ago. However, the fish tested last year came up negative — telling us the actual prevalence is at an extremely low level,” said Kris Holmes, Game and Fish spawning coordinator. “We are going to test fish again this year at a higher prevalence.”

Carl Smith, Game and Fish fish health program manager, said the lab tests about 800 samples per year for BKD, which equates to about 4,000 fish. Smith added the number of fish tested for BKD has increased since 2020 because of Wyoming’s participation in the Colorado River Fish and Wildlife Council, which is a partnership among state agencies within the Colorado River Basin. Another reason for more BKD tests is the increase of testing of wild fish populations.

“Fish managers are interested in moving and/or transplanting various fish species throughout Wyoming. These wild populations undergo the same rigorous testing regime as our hatcheries and rearing stations do, including BKD testing,” Smith said.

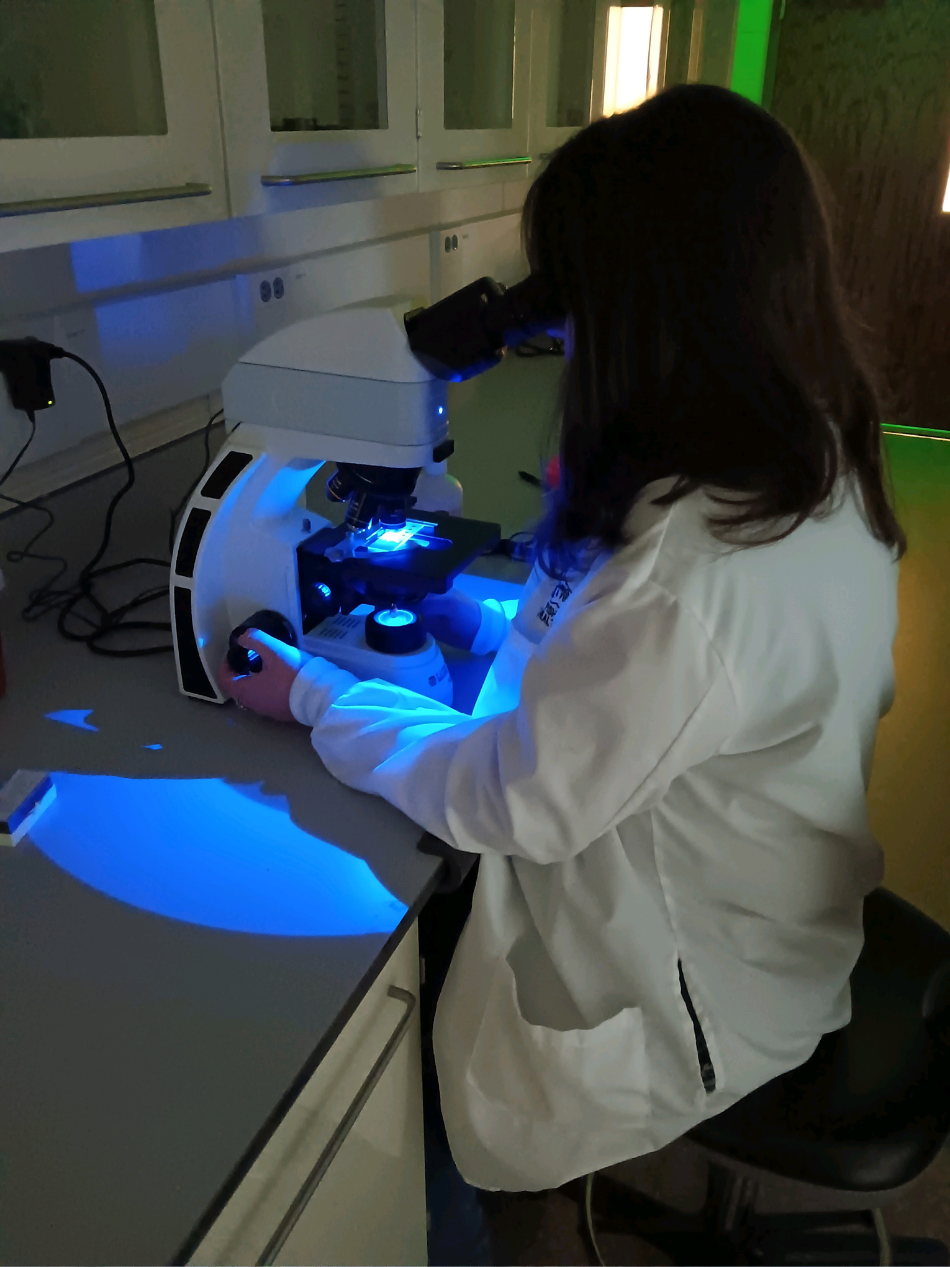

Megan Smith, laboratory scientist with the Wyoming Game and Fish Department's Fish Health Laboratory, examines a slide for possible fish pathogens. (Carl Smith, WGFD)

WHAT'S NEXT?

Continued monitoring of water quality and systems at all of Wyoming’s hatcheries, along with monitoring for pathogens in hatcheries in the wild. This isn’t new work, just continued efforts by Game and Fish. The same can be said for ways to cover open-water areas at hatcheries.

There’s also a lot of work that’s been happening for quite a while that will continue. Holmes said, for instance, that when crews go out to do a spawning operation, they arrive with clean water. In other words, they transport water from a clean, pathogen-free source. Eggs are spawned, rinsed, treated with iodine and shipped in clean water.

Protocols are in place to properly clean equipment, ranging from trucks and nets, and even boots and clothing from spawning personnel when going to and from a spawning operation. Disinfection stations are located throughout all of Wyoming’s hatcheries to prevent the spread of pathogens and diseases. This is for Game and Fish personnel and visitors.

“Over the last few years, we’ve continued to strengthen our biosecurity protocols, and we will continue to do that,” Campbell said.

Campbell added if Game and Fish knew nearly a century ago what it knows now about fish pathogens/diseases and aquatic invasive species, many of the state’s hatcheries and rearing stations would have been built differently — ranging from site locations, protecting water supplies, covering tanks/raceways and water sources.

“Now, however, it’s about how we retrofit our facilities to meet these same goals,” he said.

— Robert Gagliardi is the associate editor of Wyoming Wildlife magazine.