Aging fish

For several days during December, Andrew Nikirk, one of Sheridan’s two fisheries biologists, spent hours peering into a microscope and carefully counting. Through the lens he was viewing otoliths, inner ear bones that are used to determine the age of a fish.

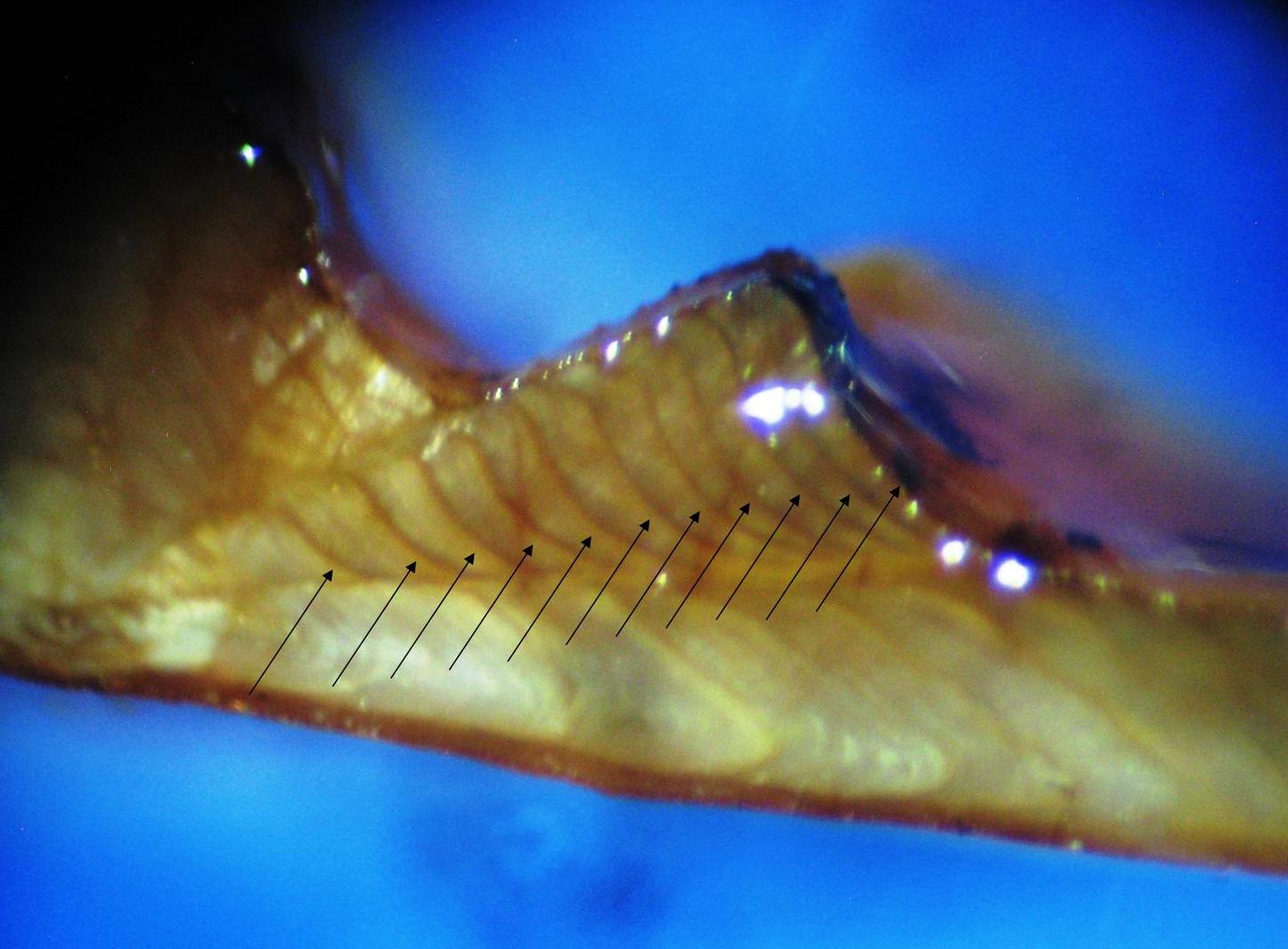

Much as a tree puts down rings during each year of its growth, otoliths also feature growth rings that indicate a fish’s age. As a fish grows quickly during the summer while food is abundant, multiple thin white bands are laid down in the bone. When metabolism slows in the winter, daily growth is reduced so lines are closer together, showing up as one larger, dark band. Therefore in most cases, each dark band counted on the bone represents one winter of a fish’s life.

The otoliths were collected from walleye during sampling that took place this summer at Keyhole Reservoir, Lake DeSmet and LAK Reservoir near Newcastle.

By studying the otoliths, biologists can get a better picture of the health of the population.

“Otolith aging is just a snapshot of how the fish are growing which is a good indication of the productivity of that water,” said Nikirk. “It is just another tool to look at to evaluate and analyze a population to see how things are going or maybe how to improve it.”

This year, the fisheries crew collected 80 otoliths from Keyhole and 38 from DeSmet. No otoliths were collected at LAK.

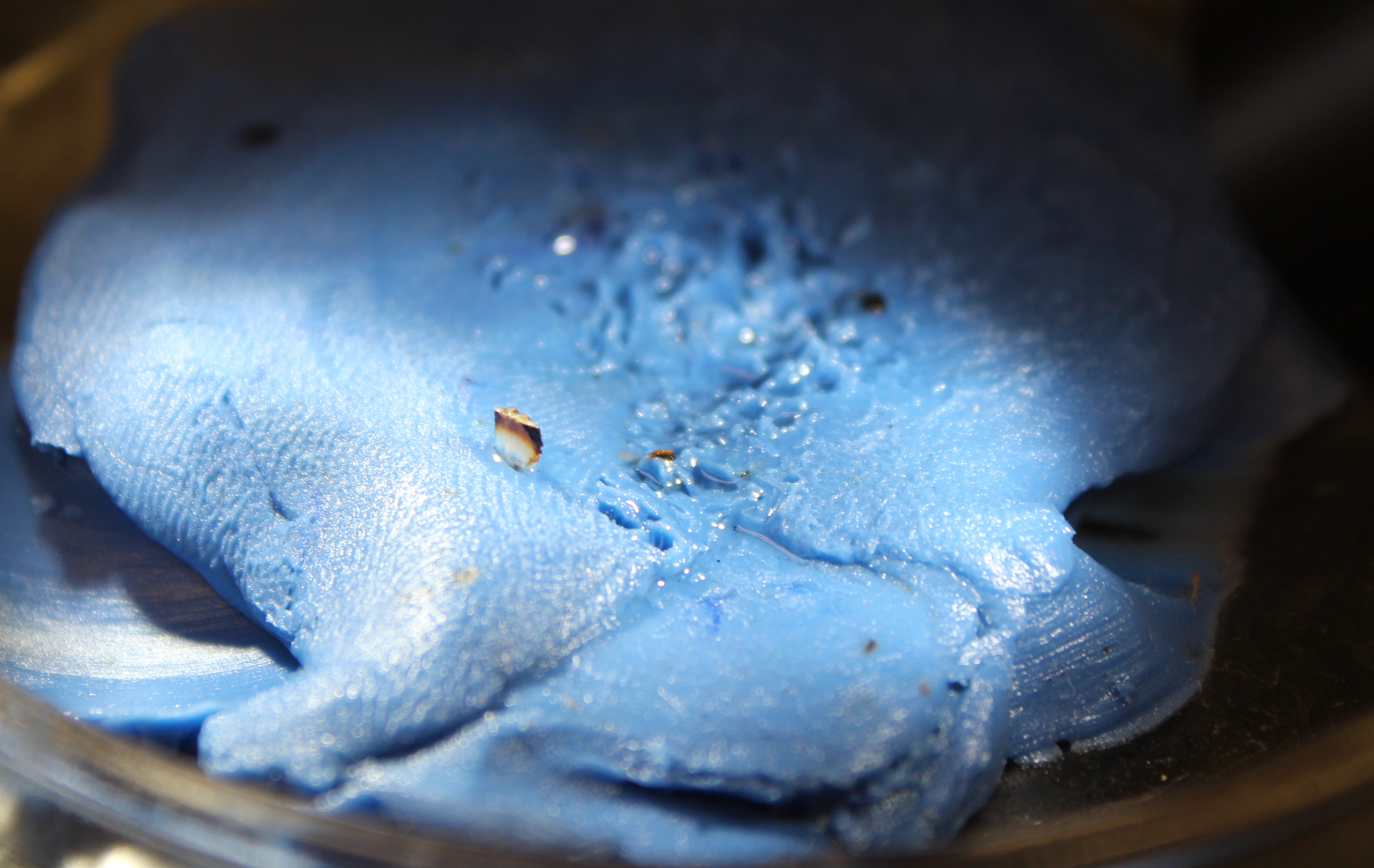

The otoliths are broken in half with a knife or by hand in a method known as ‘crack and burn’. After cracking, one bone half is lightly singed over a flame to add some color to it for the lines to stand out better.

“You cannot let it get too hot or it burns but you do want a little singeing,” said Nikirk. “Essentially you are putting a little color on white bone. Otherwise it doesn’t show up as well.”

After singeing the bone, Nikirk adds a small drop of mineral oil to make it shine and fill in the rough cracks. He then secures it upright in a clay base to view under a light and microscope.

Starting in the middle and counting the dark lines radiating outward, he can establish a close age estimate for the fish.

Biologists measure fish length while conducting surveys, but length only provides a general indication of age.

“I know a 12-inch walleye from Keyhole will be in the two to three-year-old range,” said Nikirk. “But a 19-inch walleye could be four to five or all the way to 13 or 14 years old. That is where the otolith aging comes in.”

“A fast growth rate could just be a factor of productivity in a particular water body and it could vary from year to year based on food availability, competition and other factors,” he continued. “For example, the past couple years I have seen quite a few 12-inch walleye at two years old and some three-year-old fish at 15 inches from Keyhole. That is fast growth for a walleye, so that shows me that Keyhole had good productivity of forage fish like gizzard shad, emerald shiners, spottail shiners and yellow perch for the walleye to feed on, resulting in fast growth.”

Some of the older walleye that Nikirk has seen over the years are 16 or 17 years old and these tend to be found at Lake DeSmet. He noted that Keyhole is warmer and shallower and has heavier angling pressure, so walleye don’t often make it into the older age classes. The oldest fish aged this year was estimated at 15 years old and came from Lake DeSmet.

Much as a tree puts down rings during each year of its growth, otoliths also feature growth rings that indicate a fish’s age. As a fish grows quickly during the summer while food is abundant, multiple thin white bands are laid down in the bone. When metabolism slows in the winter, daily growth is reduced so lines are closer together, showing up as one larger, dark band. Therefore in most cases, each dark band counted on the bone represents one winter of a fish’s life.

The otoliths were collected from walleye during sampling that took place this summer at Keyhole Reservoir, Lake DeSmet and LAK Reservoir near Newcastle.

By studying the otoliths, biologists can get a better picture of the health of the population.

“Otolith aging is just a snapshot of how the fish are growing which is a good indication of the productivity of that water,” said Nikirk. “It is just another tool to look at to evaluate and analyze a population to see how things are going or maybe how to improve it.”

This year, the fisheries crew collected 80 otoliths from Keyhole and 38 from DeSmet. No otoliths were collected at LAK.

The otoliths are broken in half with a knife or by hand in a method known as ‘crack and burn’. After cracking, one bone half is lightly singed over a flame to add some color to it for the lines to stand out better.

“You cannot let it get too hot or it burns but you do want a little singeing,” said Nikirk. “Essentially you are putting a little color on white bone. Otherwise it doesn’t show up as well.”

After singeing the bone, Nikirk adds a small drop of mineral oil to make it shine and fill in the rough cracks. He then secures it upright in a clay base to view under a light and microscope.

Starting in the middle and counting the dark lines radiating outward, he can establish a close age estimate for the fish.

Biologists measure fish length while conducting surveys, but length only provides a general indication of age.

“I know a 12-inch walleye from Keyhole will be in the two to three-year-old range,” said Nikirk. “But a 19-inch walleye could be four to five or all the way to 13 or 14 years old. That is where the otolith aging comes in.”

“A fast growth rate could just be a factor of productivity in a particular water body and it could vary from year to year based on food availability, competition and other factors,” he continued. “For example, the past couple years I have seen quite a few 12-inch walleye at two years old and some three-year-old fish at 15 inches from Keyhole. That is fast growth for a walleye, so that shows me that Keyhole had good productivity of forage fish like gizzard shad, emerald shiners, spottail shiners and yellow perch for the walleye to feed on, resulting in fast growth.”

Some of the older walleye that Nikirk has seen over the years are 16 or 17 years old and these tend to be found at Lake DeSmet. He noted that Keyhole is warmer and shallower and has heavier angling pressure, so walleye don’t often make it into the older age classes. The oldest fish aged this year was estimated at 15 years old and came from Lake DeSmet.

Sheridan Regional Office 307-672-7418