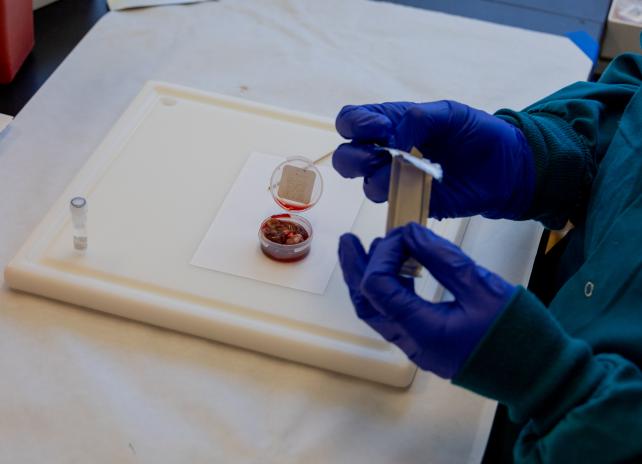

How to Collect a CWD Sample

The Wyoming Game and Fish Department collects CWD samples for testing at hunter check stations and through voluntary sample submission. You may submit a sample for CWD testing even if you are hunting in an area that was not designated as a focus area. Learn how to collect and submit a sample for testing here.

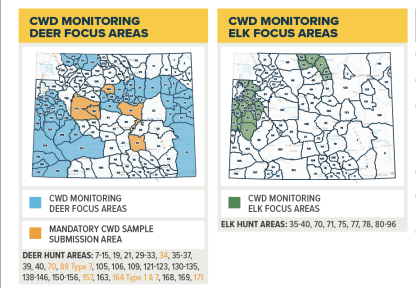

2025 CWD Focus Areas

If you hunt in a focus area selected for monitoring or mandatory sampling, you may receive additional communications about how to submit CWD samples. Your help in this effort is greatly appreciated! Please view this year's monitoring and mandatory sampling areas to determine if you may be asked to participate in surveillance efforts. Monitoring and mandatory sampling areas will be posted before hunting seasons open each year, typically by August 1.

Carcass Disposal Locations

If a hunter harvests an animal that has CWD, improper disposal of the animal's carcass can spread CWD to new areas. To minimize the possibility of transmission, Wyoming's regulations outline requirements for transporting and disposing of all big game carcasses. Regulations and approved carcass disposal locations can be found here.

-

Answer

Chronic wasting disease (CWD) is a chronic, fatal disease of the central nervous system in mule deer, white-tailed deer, elk, and moose. CWD belongs to the group of rare diseases called transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (TSEs). These disorders are caused by abnormally folded proteins called “prions.”

-

Answer

Early in the disease, animals may show no clinical signs. Later, affected animals show progressive weight loss, reluctance to move, excessive salivation, droopy ears, increased drinking and urinating, lethargy, and death. Animals will test positive for the disease long before these clinical signs appear and the majority of CWD-positive animals that are harvested appear completely normal and healthy.

-

Answer

If you see a deer or elk that looks sick, contact your local regional office. They will determine the best course of action and may send a game warden or biologist to investigate the incident.

-

Answer

Evidence suggests that CWD is transmitted via saliva, urine, feces, or even infected carcasses. Animals may also be infected through the environment via contamination of feed or pasture with CWD prions (which can persist for many years). The most likely route of exposure is through ingestion.

-

Answer

CWD was first identified in free-ranging mule deer in southeastern Wyoming in 1985, followed by elk in 1986. Based on early surveillance data and prevalence estimates, a small area in southeastern Wyoming containing the Laramie Mountain mule deer herd, South Converse mule deer herd, Goshen Rim mule deer herd and Laramie Peak elk herd was termed the "core endemic area" where we believe that CWD has been present for the longest time. Over the past 20 years, surveillance data has shown increased prevalence and distribution of CWD in Wyoming, particularly in deer. CWD is now found across most of the state, with new detections suggesting continued westward spread of the disease.

-

Answer

Recent research in Wyoming has demonstrated declines in mule and white-tailed deer populations in deer hunt area 65 due to CWD (see below for citations). These declines are in the core endemic area where prevalence is highest. In areas with lower prevalence, the effects of CWD need to be better understood. Still, they are considered additive along with other factors that can negatively affect deer populations in Wyoming (i.e. habitat loss, predation, and other diseases).

The distribution and prevalence of CWD in Wyoming elk is less than that of deer. Currently, there are no documented direct population impacts in Wyoming elk from CWD; however, Rocky Mountain National Park research suggests that CWD could impact elk populations at a higher prevalence (13%). While CWD has been found in free-ranging moose, there have been few detections, and there is no evidence that CWD is currently impacting moose populations.

-

Answer

To date, there have been no cases of CWD in humans and no direct proof that humans can get CWD. However, animal studies suggest CWD poses a risk to some types of non-human primates, like monkeys, that eat meat from CWD-infected animals. These experimental studies raise the concern that CWD may pose a risk to humans and suggest that it is important to prevent exposure to CWD. Therefore, the Centers for Disease Control and the World Health Organization recommend not consuming CWD-positive animals. The Wyoming Health Department also compiled information on human health and prion diseases. For recommendations for simple handling precautions when processing your harvested animal, visit the Carcass Disposal page.

-

Answer

- Have your harvested animal tested for CWD to help with our statewide surveillance program. See this link for information on having your harvested animal tested and sampling guides for collecting your own sample.

- Report sick deer, elk, and moose. Contact the Wyoming Game and Fish Department to report sick animals. Removing CWD-positive animals from the landscape can help minimize disease transmission.

- Be aware of carcass transport regulations that apply to animals harvested in hunt areas where CWD is known to occur.

-

Answer

The Wyoming Game and Fish Department has recorded several episodes about CWD on the Get Outside! podcast. Just search "Get Outside! CWD" on Spotify or wherever you get your podcasts.

Game and Fish also recommends the following external resources:

Chronic Wasting Disease Alliance

CWD Video Series from the Mississippi State University Deer Ecology & Management Lab, and partners

Chronic Wasting Disease Video from The Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation

Seeing is Believing from Colorado Parks and Wildlife - Part 1 | Part 2

Get Outside Podcast

Episode #2 CWD Management Plan

Episode #3 - CWD Surveillance and Monitoring

Episode #4 - Carcass Transport and Disposal

Episode #5 - Common Questions and Misconceptions about CWD

Wyoming CWD Management Plan

Wyoming Game and Fish Department has strived better to understand CWD through research and on-the-ground monitoring. We have spent years cooperating with other researchers evaluating vaccines, considering genetics, and searching for diagnostic test options while gathering over 30 years of prevalence data.