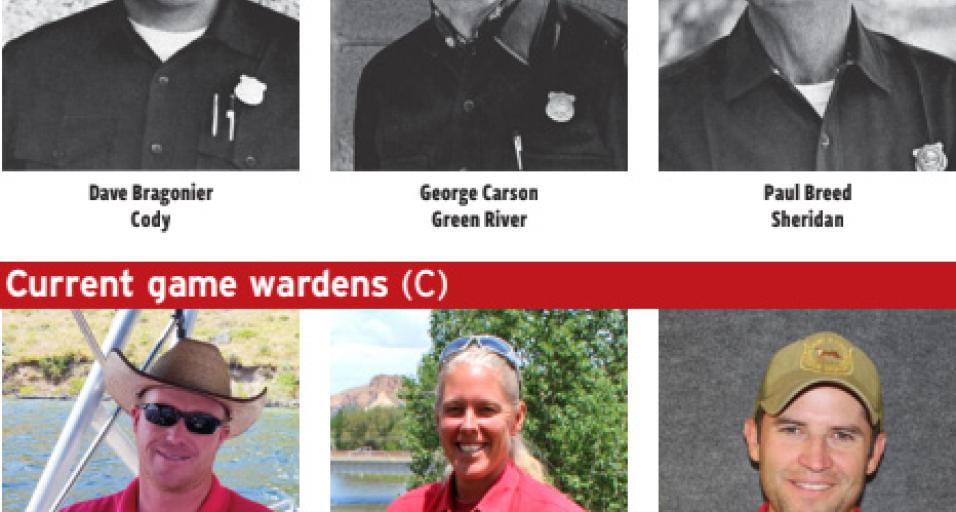

Past meets present

In the April 1973 issue of Wyoming Wildlife there was a question-and-answer story with three Wyoming Game and Fish Department game wardens. They answered thirty-five questions, mostly about wildlife violations. The magazine staff, in most cases, ran one answer with each question from a specific warden.

Three current game wardens, representing the state’s diverse regions and with a combined 60 years of experience, answered the same questions. Even after 50 years, some things remain the same with similar concerns and struggles. For other topics, it seems as if 50 years has placed wardens in completely different worlds. See how the responses compare after 50 years.

Some answers from the past and present were edited for length.

What is one of the most common hunting violations in Wyoming, and why do you think it is the most frequent problem?

Kim Olson (C): I believe one of the most common violations is failure to properly tag a game animal. It can occur accidentally and intentionally. Sometimes the excitement of getting an animal harvested overrides the idea of tagging the animal. Other times it is done deliberately in an attempt to get the animal back to town or to camp with hopes of reusing the tag on another animal or to fill the tag of another person who had purchased a license but has no intention of actually leaving the camp to go hunting.

Dustin Shorma (C): The most common violation I see in my district is hunting, fishing or collecting antlers on private land without permission. Sheridan County has an amazing wildlife resource. Unfortunately, getting access to private land is difficult and there isn’t much public land for sportspeople to spread out.

Dave Bragonier (F): Probably failure to properly tag a game animal. Some of these violators are just careless. However, other hunters will try and take the animal home on an unused tag with the forethought of going back into the field after another game animal with a clean-looking license and tag.

Do you feel most poachers plan their acts or do the majority act under spontaneous impulse when an opportunity presents itself?

Adam Hymas (C): If we consider poachers as someone who commits more serious wildlife violations, I believe many have predetermined what they will do if an opportunity arises. They may not have planned it, but they have thought about it, committed a violation in the past or been around violations previously. Generally when we catch them it has not been their first rodeo. There have also been numerous cases where alcohol consumption played a role in poor decision making.

George Carson (F): If we refer to poachers as the term that is commonly understood, we would have to say most poaching is intentional and therefore planned, albeit somewhat loosely planned in most cases.

Kim Olsen, Baggs game warden for the Wyoming Game and Fish Department, discusses a tag with hunters. (Photo by Chris Martin/WGFD)

Kim Olsen, Baggs game warden for the Wyoming Game and Fish Department, discusses a tag with hunters. (Photo by Chris Martin/WGFD)

Kim Olsen, Baggs game warden for the Wyoming Game and Fish Department, discusses a tag with hunters. (Photo by Chris Martin/WGFD)

Kim Olsen, Baggs game warden for the Wyoming Game and Fish Department, discusses a tag with hunters. (Photo by Chris Martin/WGFD)When a person witnesses a violation what should they do?

Dustin Shorma (C): Safely gather as much information as you can — location, what kind of violation, suspect information, suspect vehicle information, etc. — and contact the Stop Poaching Hotline at 1-877-WGFD-TIP. Everyone carries a cell phone. Snap a photograph of the person, vehicle, or better yet, license plate. Use mapping software such as OnX to mark a waypoint of a carcass or location. Heck, folks can even submit tips via text message by texting keyword WGFD and message to 847-411.

The sooner you contact us the faster we can start working to successfully prosecute the case.

George Carson (F): Get the facts like where the violation occurred, when it occurred, who was involved and what they did. Vehicle description, license plate number, physical description, color of clothing — anything along those lines. Report this information as soon as possible to the nearest warden or any enforcement agency.

Have you noticed any changes in the behavior of hunters during the time you have been a warden?

Dustin Shorma (C): Our society has changed to expect immediate gratification in all aspects of everyday life such as fast food, fast internet, cell phones, social media, Google, on-demand movies, etc. I have started to see this same expectation when folks are hunting or fishing.

I also see a lot of people depending more on technology while in the field. When I was a kid I never heard of anyone trying to shoot at something 1,000 yards away, wearing clothes that trap human scent, hanging trail cameras or having a scope with a built-in rangefinder that automatically corrects the crosshairs so you will hit the target. It blows my mind how far technology has come and what the next game-changing piece of equipment is. I fear the intimate connection folks have with the outdoors and knowledge field-savvy hunters usually gain through blood, sweat and tears is being lost.

Paul Breed (F): I have noticed hunters who have taken gun safety courses and who belong to good sportsmen groups are better for having done so. I believe more hunters are learning the values of wildlife and what it means to them. I have hunters report violations to me every year. This shows me they are concerned about our wildlife and the protection of the resource.

Dustin Shorma, Dayton game warden for the Wyoming Game and Fish Department, participates in a mule deer capture. (WGFD photo)

Dustin Shorma, Dayton game warden for the Wyoming Game and Fish Department, participates in a mule deer capture. (WGFD photo)

Big Piney game warden Adam Hymas makes a call on a radio. (WGFD photo)

Big Piney game warden Adam Hymas makes a call on a radio. (WGFD photo)

What species of game do poachers in your district “work on” the most and why?

Adam Hymas (C): In my area I would say elk hunters tend to have more violations than other hunters — in part due to the fact everyone who hunts generally has an elk license and plans on putting elk meat in the freezer.

Kim Olson (C): In my district poachers work on whatever seems to be most plentiful at the time, and that is probably elk right now.

Dustin Shorma (C): Elk bring out the worst in people. I am not sure what it is, maybe the challenge they present because they are big, hard to hunt and tough to kill. You can take an average, every-day citizen who normally is a good person and once you put a live elk in front of them they make incredibly poor decisions.

Paul Breed (F): Deer.

Among the violators whom you have dealt with, would you say more have poached for heads or have the majority poached for meat?

Kim Olson (C): Most of the violators I have come across have poached for the heads. Anymore, it seems if you have the money to purchase a side-by-side, spotting scope and rifle it is very likely that you can afford to buy some meat from the grocery store.

Dave Bragonier (F): Probably the majority of the violators have poached for meat or on impulse to kill something rather than for the head. However, there is an increasing illegal market for trophy-sized heads, and poaching for heads is on the increase.

What is the most difficult part of being a game warden?

Adam Hymas (C): Trying to navigate the diverse public we work for and with. Only about one-third of my time is spent on law enforcement, with the remainder spent on wildlife management, education and landowner or public contacts. We are always trying to manage wildlife responsibly for the benefit of wildlife, habitat, sportspeople, landowners and wildlife enthusiasts. Sometimes all these views do not agree on the best management practices. Many times there will be a lot of dissatisfaction from one side or another. Sometimes it's hard to not take a lot of the criticism personally.

Kim Olson (C): Being disappointed by unethical behavior can be pretty tough to deal with sometimes. I don't always get to say what I might want to, so I have to hold my tongue. Another difficult thing to deal with is the serial poachers that you know exist and you always seem to be one step behind. It can take years to catch up with some of these guys, but when they make the slip, we'll be there. Game wardens tend to be very determined and we seem to stay positive, believing that tomorrow will be our day and our time is coming. I still have unsolved cases from more than five years ago. I continue to look for a certain vehicle description. We tend to not give up easily.

Dustin Shorma (C): Working with the public is very challenging. I try my best to balance the needs of the hunting, fishing and trapping public with what is best and biologically possible for the wildlife resource. Sometimes you succeed, sometimes you don’t.

Working with the public is the most rewarding part, too. Unlike other law enforcement agencies, 98 percent of the people I deal with are not causing any problems and are out enjoying this great state we live in. I enjoy my interactions with the public and depend on them to help me do my job. The tips I have received during my career have resulted in some fantastic cases being made on some very deserving poachers. Without this help, those folks would still be out there stealing from the rest of us.

George Carson (F): People management. We are all trained in the various aspects of game, fish and habitat management, and we can more or less handle those tasks. Without the help of the general public, we can handle none of them.

Dave Bragonier (F): The game warden must make certain controversial decisions, and hope he made the right one for each situation.

Paul Breed (F): Maintaining self-control. When you have to arrest a subject that becomes belligerent, calls you unkindly names and sometimes even threatens your life, you have to remain cool and calm and use only as much force as necessary to control the subject.

— Robert Gagliardi is the associate editor of Wyoming Wildlife.