Wyoming Outdoor Hall of Fame

The Wyoming Outdoor Hall of Fame was created in 2004 by Governor Dave Freudenthal to honor those individuals, both living and posthumously, who have made significant, lasting, lifetime contributions to the conservation of Wyoming’s outdoor heritage.

Recognition is given to people who have worked consistently over many years to conserve Wyoming’s natural resources through volunteer service, environmental restoration, educational activities, audio/visual and written media, the arts and political and individual leadership. The Wyoming Outdoor Hall of Fame is designed to educate the public about and promote the significance of our state's rich outdoor heritage.

2025 Induction Ceremony

The Wyoming Outdoor Hall of Fame induction ceremony took place in March 2025 at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West in Cody.

Submit a Nomination

The Committee will now accept nominations for the November 2026 induction ceremony. The deadline to submit a nomination is March 2026.

Hall of Fame Nomination packet

Youth Conservationist of the Year Nomination Packet

Have questions? Please call 307-777-4637 for more information.

Get involved, become a sponsor

The outdoor industry is crucial for the state of Wyoming and the committee wants to continue to honor the people who make it possible.

All donations are tax deductible.

Have questions? Please call 307-777-4637 for more information.

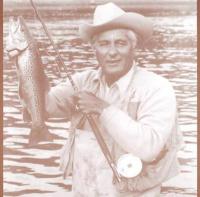

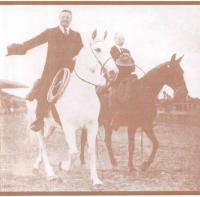

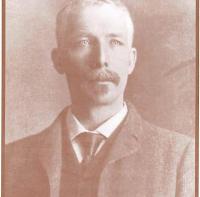

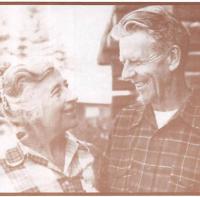

Past Hall of Fame Inductees

President Theodore Roosevelt

D.C. Nowlin

Olaus & Mardy Murie

Frank and Lois Layton

Calvin King