Life Underground

Dark caverns and tight spaces. It’s enough to send a shiver down one’s spine. Other than spelunkers and the gutsiest of climbers, most people easily avoid these kinds of spaces.

Yet for Wyoming’s wildlife, the mounds of loam and humus, rich clay and glistening mud present opportunity — home. Of the more than 800 animal species in Wyoming, only a fraction reside underground. From lovingly dug dens, utilitarian burrows and humble hibernacula, being underground presents a multitude of advantages in Wyoming.

The author spent time in Teton County capturing boreal toads for research (Photo by Jesica Grant/WGFD)

With insulation from the cold and elements, rich nutrients, diverse foods, oxygen, moisture and a convenient escape from predators, soil is a diverse ecosystem supporting and carrying layers of life. Critters can cache goodies in soil, use burrows to peer out and survey their surroundings, hide from predators and lay eggs in the ground. Subterranean experts may hibernate or overwinter in prolonged naps before emerging refreshed or in the case of insects, transformed into adults. Holding billions of species from bacteria a micron long to the roots of the great redwood tree, soil is a big deal, and the wildlife that depends on living underground for solace are tired of being dragged through the dirt.

Totally cool

I won’t forget my first meeting with Dr. Erin Muths of the U.S. Geological Survey Science Center in Fort Collins, Colorado.

“Have you ever caught a toad before? No matter, it’s like catching a slow moving potato. You’ll be fine,” she said.

A spunky, enthusiastic researcher, Muths was full of personality beaming out of her four-foot-seven-inch frame. Eager to learn and find a position to cover my graduate expenses before my own fieldwork that summer, I was a “toad girl.”

I went to Teton County to experience the life of a herpetology technician, one of many to assist with the years of continued research on the boreal toad, also known as the Western toad. That experience is what led to my fascination with other toads, most notably one that holds the title of the most endangered amphibian in North America — and it can only be found in the Cowboy State.

Efforts continue to recover the Wyoming toad. The last known wild population of this species is in Albany County. (Photo by Mindy Mead)

The Wyoming toad (Anaxyrus baxteri), also called Baxter’s toad, is a warty, yes, potato-like amphibian. In hues of murky green with a buff, cream underside, this charismatic toad is distinguished from other toads by the shape of the two parallel ridges sitting vertically between the eyes. It is between half-an-inch to 2.5 inches long and spends several months of the year hibernating in a small, cozy chamber beneath the frost line. The hibernaculum protects the Wyoming toad from harsh Wyoming winters, freezing weather and hungry predators. Only when daytime temperatures reach 70 degrees in May to June will the Wyoming toad emerge from its snug hibernaculum to breed in nearby warm and shallow water.

However, there are a lot of issues that have led to a population decline of the Wyoming toad such as disease, chytrid fungal infections and changes to water quality. The last known wild population of the Wyoming toad is federally protected within the Mortenson Lake National Refuge in Albany County. Thought to be extinct in 1985-87, a small population was discovered in 1987 in the refuge, but its numbers are still struggling. In 2001, the Wyoming Toad Recovery Team was formed. The team consists of members from Game and Fish, the University of Wyoming, Association of Zoos and Aquariums, Laramie Rivers Conservation District, Wyoming Natural Diversity Database, private landowners and ranchers, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, National Fish Hatchery System, Arapaho National Wildlife Refuge in Colorado and representatives from other organizations. These groups and individuals work together to recommend management and recovery plans for the Wyoming toad.

Outside of the wild population, several captive breeding programs involving the University of Wyoming’s Red Buttes Biological Laboratory, Saratoga National Fish Hatchery and six zoos throughout the country have helped the Wyoming toad population jump to new heights since 1993. The toad has also been reintroduced to some private properties as part of a Safe Harbor program for endangered species.

“The biggest challenge the Wyoming toad faces is amphibian chytrid fungus,” said Wendy Estes-Zumpf, Game and Fish herpetologist and Wyoming Toad Recovery Team leader. “The Wyoming Toad is highly susceptible to the pathogen and we see population crashes immediately following spikes in chytrid fungus prevalence. Game and Fish works closely with captive breeding facilities, researchers, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, city and county personnel, and landowners to research methods that will help the toads combat chytrid infections, to secure high-quality habitat for the toad and to support populations at reintroduction sites through captive breeding.”

Chytrid fungus attacks the moist skin of amphibians. When amphibians are infected with chytrid fungus, their skin thickens – making it harder for them to breathe and reducing their ability to fight off infections. Most amphibians with chytrid fungal infections do not survive. The few that do have better chances of passing on genes and traits that are better equipped to fight chytrid infections.

While Wyoming toad populations may be improving, amphibian chytrid fungal infection is the largest, active threat to more than 350 species of amphibians throughout the world. Estes-Zumpf said chytrid is highly pervasive because it must stay wet to survive, and anything that moves water can spread the fungus. In order to limit chytrid infections, those working in and around freshwater, including anglers, trappers, hunters and other recreationists are encouraged to clean and dry anything that comes in contact with water. Estes-Zumpf also said rinsing gear with a 10 percent bleach solution will kill the fungus.

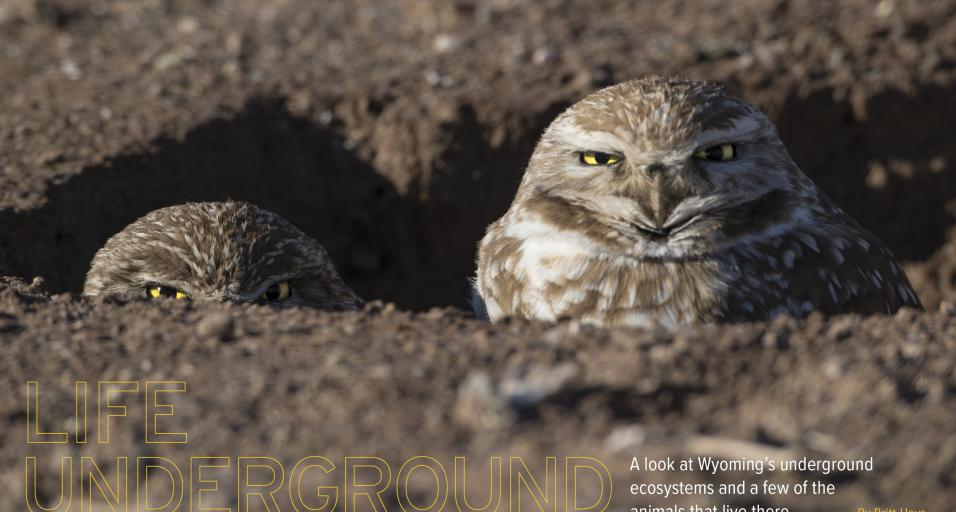

Burrowing owls live underground, often in burrows excavated by prarie dogs. (Photo by Tim Christie)

Owl about that?

For most people, birds bring thoughts of flying through the air and building nests above the ground and out of reach. But not all birds take up residence high above our heads. Some, like the burrowing owl, live underground.

Burrowing owls (Athene cunicularia) stand 19-25 centimeters tall and are plucky, leggy raptors. Like their name suggests, the owls live in burrows — but not necessarily ones they dig themselves. Peering with enormous yellow eyes, these sand-colored owls usually move into burrows already dug by prairie dogs, ground squirrels, badgers, and other burrowing mammals. Their perfect lookout, nesting spot and food cache are dependent on the longevity of prairie dogs and the grassland and prairie habitats that support them. These owls will occasionally excavate their own burrows, but are most likely to repurpose prairie dog burrows in Wyoming.

These little owls aren’t year-round residents of the state. Like many birds, they leave for warmer locales during the winter. They leave Wyoming in September or October and may stop in Colorado, Arizona and Texas en route to their winter grounds. For years, researchers thought many of Wyoming’s burrowing owls migrated to Mexico. Using transmitters, researchers set out to learn more about where the state’s burrowing owls go when the temperatures start to drop. The research paid off in 2019-2020 when one owl confirmed what researchers had suspected by breaking migration record distances for the species. A female burrowing owl left her nest north of Gillette in fall 2019 and migrated 2,200 miles to winter northeast of Acapulco, Mexico. The owl then returned to the same nest location in Wyoming in May 2020, completing a 4,500-mile round trip.

Burrowing owls can arrive in Wyoming to breed as early as March. During breeding season, the owls use the burrows to build nests. The nests are built in the back of their burrow, often with cow manure and grasses. They also have the unusual behavior of decorating the outside of their burrow with manure and other objects, sometimes including bits of human trash. The burrow then protects their smooth, white eggs. After about a month of incubation, fuzzy, grey owlets hatch. Young chicks appear outside the nest in mid-June, but do not fully fledge until the end of July. Both parents feed young birds. Burrowing owls eat mice, voles, insects, amphibians, earthworms, bats and small songbirds.

Gopher the burrow

Gophers are similar to voles, prairie dogs and ground squirrels. Gophers consume grasses, shrubs and forbs pulled into their tunnels from above ground. They burrow in all soil types and leave behind mounds of dirt, holes and tunnels in their wake.

The Wyoming pocket gopher (Thomomys clusius) is only found in the Cowboy State. Distributed in south-central Wyoming in Sweetwater and Carbon counties, the Wyoming pocket gopher is rarely seen. It spends the majority of its life underground in a maze of tunnels and chambers dug deep into well-drained, clay soils. Wyoming pocket gophers make soil-packed tubes called eskers near the surface that appear after the last snowmelt. Below the eskers lie the deposit of scat or feces about 12 inches below ground, similar to a cesspool. Deeper is a chamber used for food storage and nesting. One to four gopher pups are born late-spring to early-summer before they leave the nest to create their own burrow systems in June-July. Only one litter of pups are born each year, unlike other rodents that are proliferate breeders.

Gophers create complex burrow systems that can spread hundreds of feet underground. Each adult gopher uses its claws and long, protruding incisors to burrow, trim roots and move rocks creating about one to three new mounds per day. Pushing soil to the surface with their chest and forefeet like a persistent linebacker, a single gopher can move more than two tons of soil to the surface every year. Each gopher assists in creating a healthy mix of soils by improving aeration, which allows greater oxygen and gas exchange and improved water absorption in plant roots. Gophers mix organic matter, help lessen soil compaction and bring soil to the surface where it is weatherized to create new, nutrient-rich soil.

Living underground has its challenges for Wyoming’s wildlife. Several species develop adaptations to low light, reducing or losing vision and hearing and sometimes organs required for perceiving light disappear. Vestigial or nonfunctioning organs, like eyes, may lead to other senses strengthening. For example, in Wyoming’s only mole species, the eastern mole, vision is almost nonexistent. Most moles’ eyes are covered in thin skin where they can determine changes in light but not details. With reduced vision, moles rely on feeling vibrations in the ground or their strong sense of smell to avoid predators and find food and mates.

Similarly, of the eighteen species of bats found in Wyoming, most have vision adapted to darkened skies. Some bats in the genus Myotis and Townsend’s big-eared bats roost in underground caves in the Bighorn Mountains. Their eyes, which can see better than most humans, are packed with special photoreceptor cells called rods that detect light and dark while cone cells in the bats’ retinas help determine color. Bats also utilize echolocation or waves of high-pitch sound that bounce off objects such as cave walls, predators and even flying insects to help the bat determine distances and shapes.

To be underground is to live with the pulse of the Earth. Whether burrowing, tunnel vision, caches or dens under the harshest of situations, Wyoming’s Wildlife continues to prevail.

— Britt Hays is a volunteer and hunter education instructor for the Wyoming Game and Fish Department. They enjoy being outside and hiking, this is their first contribution to Wyoming Wildlife.

Photographer Info

Tim Christie